With the benefit of 150 years of hindsight, we can recognize today that the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad in 1869 was of greater importance to the people of the United States, culturally, socially, and economically, than the inauguration of steamship service across the Atlantic or the laying of the Atlantic Ocean telegraph cable.

In an era of interstate highways and quick air travel, it is difficult to imagine just how isolated those parts of the United States farthest from the oceans were, even as late as the mid-19th century. That most optimistic of our early presidents, Thomas Jefferson, referred to the “immense and trackless deserts” in the Louisiana Purchase. The explorer Zebulon Pike compared these lands to “the sandy wastes of Africa.” Daniel Webster declared Wyoming Territory “not worth a cent,” being, moreover, “a region of savages, wild beasts, shifting sands, whirlwinds of dust, cactus, and prairie dogs.”

Maps of North America as late as 1900, three decades after the railroad connecting New York with San Francisco had been launched, showed 500,000 square miles ominously labeled “Great American Desert,” a name invented 75 years earlier by a government surveyor. This wilderness covered nearly one-sixth of the 45 States of the young American republic — along with the yet untamed territories of Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona, lands admitted to the Union only after the turn of the twentieth century.

It was Jefferson who deserve credit for being the first to take action towards opening a commercial route between the Eastern states and the Pacific. While he was in France in 1779 as United States Minister at Versailles, he asked John Ledyard to conduct a survey for him, but Ledyard was unable to carry it out. For the next seven decades, a distinguish line of far-sighted Americans sought to find a way to bridge the American West with the American East, and their stories are preserved in a handful of excellent histories of the 19th century.

Accounts of the creation of the Panama Canal and the forging of the trans-continental railroad were best sellers in the Roosevelt and Taft administrations. No more. Sadly, we have forgotten this part of the American fairy tale. And so it was with pleasure that I got a sense of the transformative nature of the rails linking the two coasts of the North American continent from William Francis Bailey’s The Story of the First Trans-Continental Railroad, (Pittsburgh: 1906), The Pittsburgh Printing Company. I read the book on a Kindle, downloaded from Project Gutenberg. I also downloaded a facsimile copy of the book itself from the Internet Archive so that I could look at the text and “feel” the book.

This is a tale full of eccentric and visionary characters, including Asa Whitney, dubbed the “Father of the Pacific Railway.” He was an American merchant with wide overseas experience, mainly in China. He proposed to Congress that the United States deed to him a strip of land sixty miles wide, the railroad to be its spine, from Lake Michigan to the Pacific Coast. Whitney proposed to use proceeds from “colonizing” (his word) this windfall of land with European immigrants (to whom he would sell land adjoining the railroad) to pay for the tracks, retaining whatever surplus remained for his private fortune. Whitney was indefatigable, travelling from Maine all the way to the reaches of the Missouri River at a time when visiting the Missouri was akin to exploring the Nile.

Though the Senate Committee On Public Lands approved Whitney’s proposal in 1848, the bill “Authorizing Asa Whitney, his heirs or assigns, to construct a railroad from any point on Lake Michigan or the Mississippi River he may so designate, in a line as nearly straight as practicable, to some point on the Pacific Ocean where a harbor made be had” failed a vote by the full Senate mainly because it was deemed, along with the $4,000 yearly salary Whitney demanded, simply too rich a deal for Whitney.

A Missouri senator opposed the measure as one that would “give away an empire larger in extent than eight of the original states with an ocean frontage of sixty miles, with contracting powers and patronage exceeding those of the president of the United States.” It was a fair criticism. Asa Whitney did not get his “empire.” Had Whitney succeeded in his plan, his “heirs and assigns” would now own more American acreage than anyone other than the Federal government itself. Congress later decided to undertake the railroad as a national venture, not a private undertaking controlled by a single private citizen.

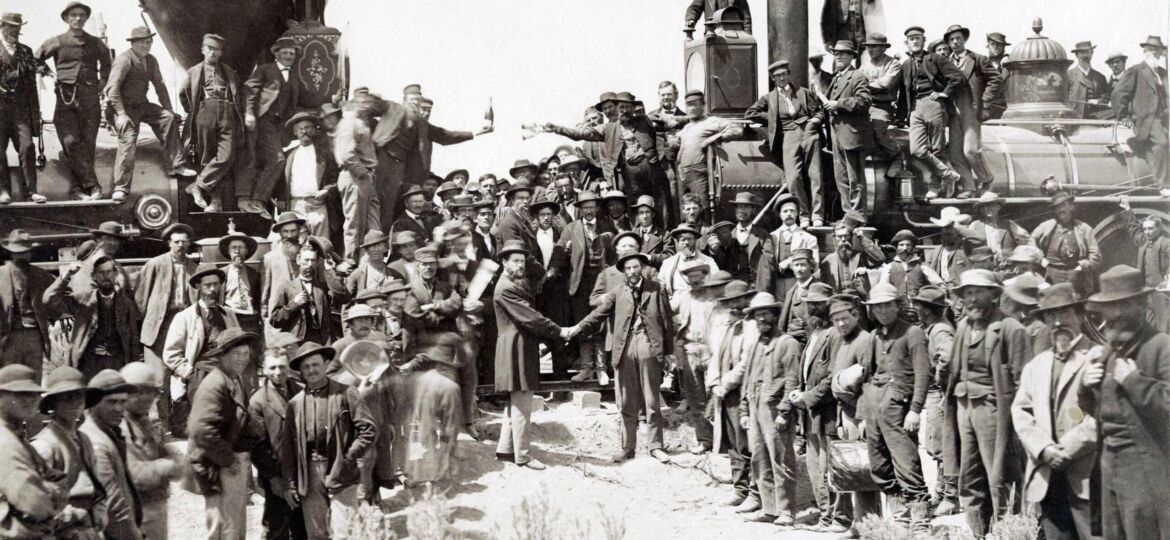

So what in fact happened to link the two coasts? What precisely do we mean by the “Trans-Continental Railroad”? It appears first only as a dream in the minds of men like Abraham Lincoln and his predecessors, often called “the overland route to the Pacific Ocean” or the “Pacific Railroad.” In that era, it was as ambitious a technological feat as the moon landing a century later. It required laying some 1,905 miles of contiguous track, starting in 1863 and continuing at a frenetic pace for six years, capped by a ceremony at Promontory Summit in Utah on May 10, 1869, a meeting almost religious in its intensity, in which the last spike (this one made of silver, and prudently removed the same day for exhibition at railroad headquarters!) was slammed into the final tie to conjoin the eastbound with the westbound tracks. Soon, a locomotive could pull a long train from the port of New York to the port of San Francisco.

As the cars began to move east and west, the nation suddenly had a speedy, reliable, and inexpensive mechanized technology to move people and cargo anywhere in the country within access, by horse or cart, of the new stations along the rail route. The railroad “shrank the nation” and made it possible for Horace Greeley and other newspaper philosophers of that era to reasonably suggest to claustrophobic Easterners that they “Go West” to make their fortunes. Before the railroad, that meant taking nine months or more in a mule-drawn cart to reach the Pacific. In the decades after the linkinh of the Atlantic and Pacific coasts by rail, distant and sparsely settled “territories” were admitted to the Union as new states, greatly adding to America’s size and prestige.

Bailey’s narrative is graceful and informative. It would be hard to overstate the significance of the trans-continental railroad as a feat of technology and astute economic development, surpassing, surely, the digging of the Erie Canal in the 1820s and the creation of that spider’s skein of rails crisscrossing the East Coast states while the American West was still considered “wild” and as unexplored as Central Africa.

It was a magnificent highway for commerce and travel that led directly to the settlement and incorporation of California, Nevada, Oregon, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming as states in the ever-expanding American republic.

Bailey’s history is also concise, a mere 140 pages in the lovely Pittsburgh Press edition recreated in electronic format by Google. What I most savored about Bailey’s writing was the sense of excitement that he conveys about this incredible re-invention of America, akin to the excitement I myself felt as a teenager watching the moon missions unfold on CBS television.

This book should be read and reread not as an onerous task, reacquainting ourselves with an important chapter in American history, but simply because it is gripping and fun. It’s a story that deserves to be fresh in our consciousness of our country and the people who settled it.

AUTOPOST by BEDEWY VISIT GAHZLY